Shark attacks in Australia: where is it safest to swim and what times should I avoid?

While the overall risk of a shark attack remains low, experts say warmer waters, various weather events, shifting prey and busier coastlines can increase the risk

Featured interviews, news coverage, and public engagement in marine science and conservation.

While the overall risk of a shark attack remains low, experts say warmer waters, various weather events, shifting prey and busier coastlines can increase the risk

Epaulette sharks can reproduce without any measurable increase in energy use, stunning researchers who expected egg-laying to be costly. Scientists tracked metabolism, blood, and hormone levels through the entire reproductive cycle and found everything stayed…

New South Wales has experienced the highest number of shark attacks for January across the state in the last decade, according to the Australian Shark Incident Database.

Surfer taken to hospital with minor injuries after latest shark attack at Point Plomer beach on mid-north coast

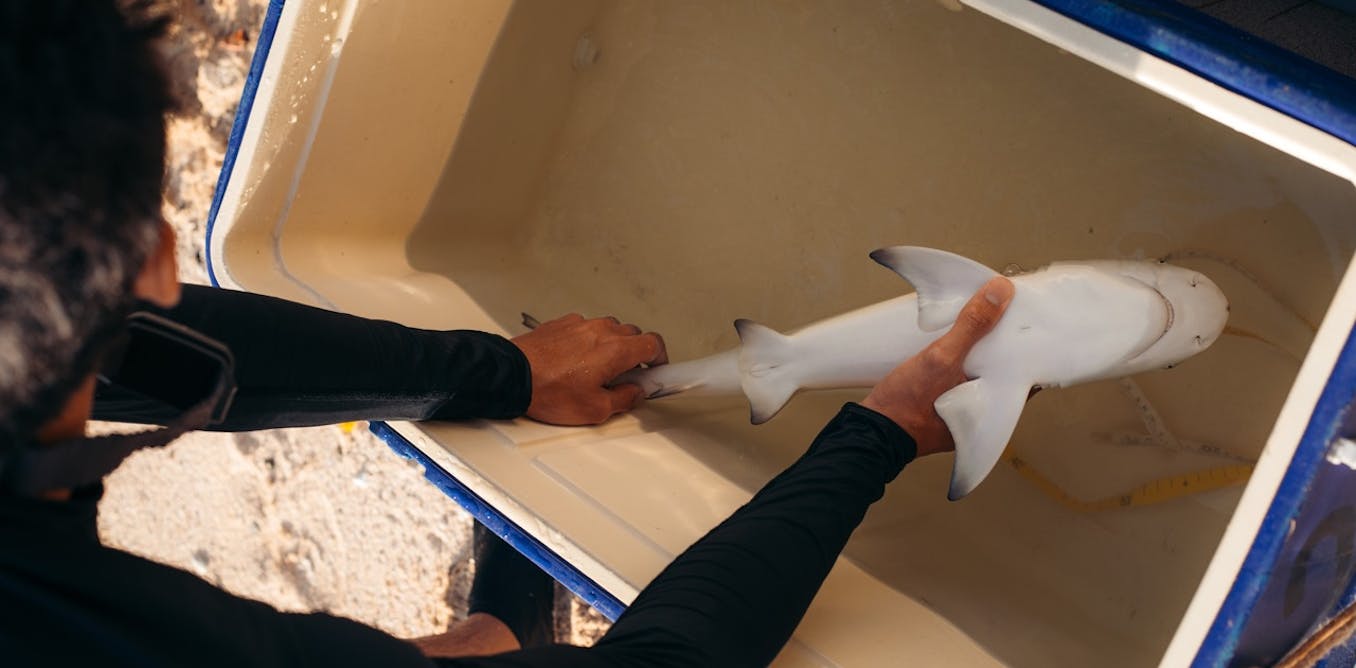

Known best for their ability to "walk" on the sand and coral where they usually live, new research shows epaulette sharks could also defy assumptions in other ways.

From 2040 onwards the average year for marine ecosystems is likely to be more extreme than the worst years experienced up until 2015, researchers say

Rachel Moore Imagine watching your favourite nature documentary. The predator lunges rapidly from its hiding place, jaws wide open, and the prey … suddenly goes limp. It looks dead. For some animals, this freeze response – called “tonic immobility” – can be a lifesaver. Possums famously “play dead” to avoid predators. So do rabbits, lizards, snakes, and even some insects. But what happens when a shark does it? In our recent study, we explored this strange behaviour in sharks, rays and their relatives. In this group, tonic immobility is triggered when the animal is turned upside down – it stops moving, its muscles relax, and it enters a trance-like state. Some scientists even use tonic immobility as a technique to safely handle certain shark species. But why does it happen? And does it actually help these marine predators survive? The mystery of the ‘frozen shark’ Despite being well documented across the animal kingdom, the reasons behind tonic immobility remain murky – especially in the ocean. It is generally thought of as an anti-predator defence. But there is no evidence to support this idea in sharks, and alternative hypotheses exist. We tested 13 species of sharks, rays, and a chimaera — a shark relative commonly referred to as a ghost shark — to see whether they entered tonic immobility when gently turned upside down underwater. Seven species did, but six did not. We then analysed these findings using evolutionary tools to map the behaviour across hundreds of million years of shark family history. So, why do some sharks freeze? Tonic immobility is triggered in sharks when they are turned upside down. Rachel Moore Three main hypotheses There are three main hypotheses to explain tonic immobility in sharks: Anti-predator strategy – “playing dead” to avoid being eaten Reproductive role – some male sharks invert females during mating, so perhaps tonic immobility helps reduce struggle Sensory overload response – a kind of shutdown during extreme stimulation. Our results don’t support any of these explanations. There’s no strong evidence sharks benefit from freezing when attacked. In fact, modern predators such as orcas can use this response against sharks by flipping them over to immobilise them and then remove their nutrient-rich livers – a deadly exploit. The reproductive hypothesis also falls short. Tonic immobility doesn’t differ between sexes, and remaining immobile could make females vulnerable to harmful or forced mating events. And the sensory overload idea? Untested and unverified. So, we offer a simpler explanation. Tonic immobility in sharks is likely an evolutionary relic. A case of evolutionary baggage Our evolutionary analysis suggests tonic immobility is “plesiomorphic” – an ancestral trait that was likely present in ancient sharks, rays and chimaeras. But as species evolved, many lost the behaviour. In fact, we found that tonic immobility was lost independently at least five times across different groups. Which raises the question: why? In some environments, freezing might actually be a bad idea. Small reef sharks and bottom-dwelling rays often squeeze through tight crevices in complex coral habitats when feeding or resting. Going limp in such settings could get them stuck – or worse. That means losing this behaviour might have actually been advantageous in these lineages. So, what does this all mean? Rather than a clever survival tactic, tonic immobility might just be “evolutionary baggage” – a behaviour that once served a purpose, but now persists in some species simply because it doesn’t do enough harm to be selected against. It’s a good reminder that not every trait in nature is adaptive. Some are just historical quirks. Our work helps challenge long-held assumptions about shark behaviour, and sheds light on the hidden evolutionary stories still unfolding in the ocean’s depths. Next time you hear about a shark “playing dead”, remember – it might just be muscle memory from a very, very long time ago. Jodie L. Rummer receives funding from the Australian Research Council. She is affiliated with the Australian Coral Reef Society, as President. Joel Gayford receives funding from the Northcote Trust.

Rachel Moore From hand-sized lantern sharks that glow in the deep sea to bus-sized whale sharks gliding through tropical waters, sharks come in all shapes and sizes. Despite these differences, they all face the same fundamental challenge: how to get oxygen, heat and nutrients to every part of their bodies efficiently. Our new study, published today in Royal Society Open Science, shows that sharks follow a centuries-old mathematical rule – the two-thirds scaling law – that predicts how body shape changes with size. This tells us something profound about how evolution works – and why size really does matter. What is the two-thirds scaling law? The basic idea is mathematical: surface area increases with the square of body length, while volume increases with the cube. That means surface area increases more slowly than volume, and the ratio between the two – crucial for many biological functions – decreases with size. This matters because many essential life processes happen at the surface: gas exchange in the lungs or gills, such as to take in oxygen or release carbon dioxide, but also heat loss through skin and nutrient uptake in the gut. These processes depend on surface area, while the demands they must meet – such as the crucial task of keeping the body supplied with oxygen – depend on volume. So, the surface area-to-volume ratio shapes how animals function. Whale sharks are as big as buses, while dwarf lanternsharks (pictured here) are as small as a human hand. Chip Clark/Smithsonian Institution Despite its central role in biology, this rule has only ever been rigorously tested in cells, tissues and small organisms such as insects. Until now. Why sharks? Sharks might seem like an unlikely group for testing an old mathematical theory, but they’re actually ideal. For starters, they span a huge range of sizes, from the tiny dwarf lantern shark (about 20 centimetres long) to the whale shark (which can exceed 20 metres). They also have diverse shapes and lifestyles – hammerheads, reef-dwellers, deep-sea hunters – each posing different challenges for physiology and movement. Plus, sharks are charismatic, ecologically important and increasingly under threat. Understanding their biology is both scientifically valuable and important for conservation. Sharks are ecologically important but are increasingly under threat. Rachel Moore How did we test the rule? We used high-resolution 3D models to digitally measure surface area and volume in 54 species of sharks. These models were created using open-source CT scans and photogrammetry, which involves using photographs to approximate a 3D structure. Until recently, these techniques were the domain of video game designers and special effects artists, not biologists. We refined the models in Blender, a powerful 3D software tool, and extracted surface and volume data for each species. Then we applied phylogenetic regression – a statistical method that accounts for shared evolutionary history – to see how closely shark shapes follow the predictions of the two-thirds rule. Sharks follow the two-thirds scaling rule almost perfectly, as seen in this 3D representation. Joel Gayford et al What did we find? The results were striking: sharks follow the two-thirds scaling rule almost perfectly, with surface area scaling to body volume raised to the power of 0.64 – just a 3% difference from the theoretical 0.67. This suggests something deeper is going on. Despite their wide range of forms and habitats, sharks seem to converge on the same basic body plan when it comes to surface area and volume. Why? One explanation is that what are known as “developmental constraints” – limits imposed by how animals grow and form in early life – make it difficult, or too costly, for sharks to deviate from this fundamental pattern. Changing surface area-to-volume ratios might require rewiring how tissues are allocated during embryonic development, something that evolution appears to avoid unless absolutely necessary. But why does it matter? This isn’t just academic. Many equations in biology, physiology and climate science rely on assumptions about surface area-to-volume ratios. These equations are used to model how animals regulate temperature, use oxygen, and respond to environmental stress. Until now, we haven’t had accurate data from large animals to test those assumptions. Our findings give researchers more confidence in using these models – not just for sharks, but potentially for other groups too. As we face accelerating climate change and biodiversity loss, understanding how animals of all sizes interact with their environments has never been more urgent. This study, powered by modern imaging tech and some old-school curiosity, brings us one step closer to that goal. Jodie L. Rummer receives funding from the Australian Research Council. She is affiliated with the Australian Coral Reef Society, as President. Joel Gayford receives funding from the Northcote Trust.

Jodie Rummer: For the love of sharks - Oceanographic Oceanographic Magazine

These parasitic sharks glow in the dark and are known to have a go at anything they come across, despite their small size