It’s one of biology’s oldest assumptions: making babies is expensive. Whether you’re a fish, a bird, a reptile, or a human, reproduction draws heavily on energy reserves. Building yolk, forming tissues, maintaining pregnancy or producing eggs — it all adds up.

But new research led by Dr Carolyn Wheeler, Dr Jodie Rummer, Dr Cynthia Awruch, and Dr John Mandelman has uncovered something extraordinary. A small, resilient carpet shark from the Great Barrier Reef appears to be doing the impossible: laying eggs without any measurable rise in metabolic cost.

This surprising result is the focus of a recent Biology Open paper, “Assessing the metabolic and physiological costs of oviparity in the epaulette shark (Hemiscyllium ocellatum)”, and the centrepiece of a lively episode of the Athletes of the Reef podcast. Together, they offer a rare look at reproductive physiology in a shark species perfectly adapted to life on the reef — and they challenge long-held assumptions about energy budgets in marine animals.

Why epaulette sharks?

The epaulette shark is a charismatic little reef dweller known for its ability to tolerate low oxygen and even “walk” across sand flats. They are also an ideal model for physiology studies. Females lay a single egg case per uterus at a time, and each reproductive cycle is fast — roughly 19 days on average at 25 °C, according to Wheeler et al.

That speed, combined with their amenability to captive care, means scientists can track egg production from start to finish under controlled conditions.

In the podcast, Dr Rummer explains why this species is so valuable: the epaulette shark’s tidy, predictable reproductive rhythm gives researchers a unique window into the full egg-laying cycle — from pre-encapsulation, to the formation of the leathery egg case, to oviposition.

Putting reproduction on the metabolic “treadmill”

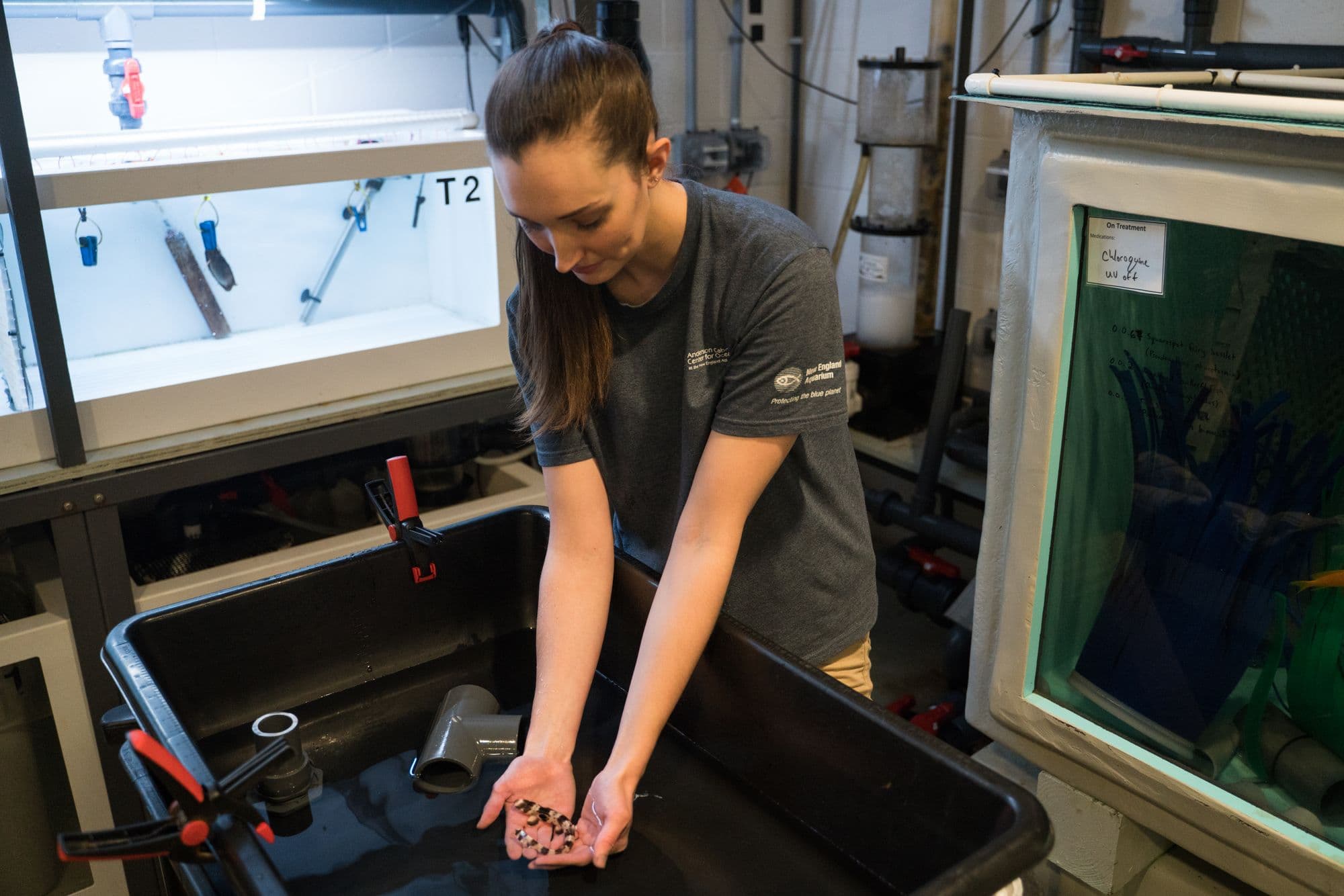

For nearly two years, the team monitored five female sharks housed individually at James Cook University’s Marine and Aquaculture Research Facility. Using intermittent-flow respirometry, they measured oxygen uptake (MO₂), a standard proxy for metabolic rate. They took measurements during three key stages:

- Pre-encapsulation – before the egg case begins to form

- Encapsulation – when the tough keratin-collagen case is being produced

- Post-oviposition – the 48 hours after the egg is laid

The expectation was clear: metabolic rate should spike during the energetically costly encapsulation phase and then drop afterwards.

But that isn’t what happened.

The shock: a flat metabolic line

Across 37 respirometry trials, Wheeler’s team found no detectable rise in routine metabolic rate during the egg-forming phase. Metabolism remained steady before, during, and after egg production — even though the sharks laid 196 egg cases across 98 cycles.

This lack of a measurable metabolic cost is astonishing. Bomb calorimetry of embryos suggests that producing an egg should be energetically expensive. Yet the real-time physiology told a different story.

Blood markers also remained stable: hematocrit, haemoglobin, and MCHC showed no substantial changes. Steroid hormones — estradiol and progesterone — barely shifted. Only testosterone exhibited a brief early-cycle peak, likely acting as a signal to kickstart ovulation.

In the podcast, Dr Rummer laughs about how counter-intuitive this seems: “It sounds like violating the laws of thermodynamics.” And yet, the data held up.

How can egg-laying be so cheap?

Two leading hypotheses emerge — both explored in the podcast and supported by the paper.

1. Income breeding: pay as you go

In the wild, epaulette sharks breed seasonally and likely rely on stored energy reserves (“capital breeding”). But in the lab, where temperatures and food availability were stable year-round, the sharks may have switched to an “income breeding” strategy.

They simply fuelled egg production directly from their regular meals.

This would spread the cost over many small daily metabolic expenditures rather than concentrating it in a measurable burst. In other words, the “bill” was quietly deducted from everyday intake.

2. A tiny gland inside a big shark

The oviducal gland — the organ that secretes the egg case — is small. Even if that gland ramps up its energy use during encapsulation, its demand may be drowned out by the baseline metabolic noise of the whole animal.

The paper notes that because these glands are small relative to total body mass, any increase in oxygen consumption may be too subtle to detect at the whole-animal scale.

This suggests the cost is real, but localised.

What this means for shark resilience

In the podcast, Dr Rummer connects these findings to broader climate-change concerns. Many marine species must choose between survival and reproduction under stress. If reproduction is energetically cheap for epaulette sharks, they may maintain egg output even in warming or oxygen-poor environments — as long as food remains available.

But there is a warning: if this species relies heavily on daily intake to fuel reproduction, disruptions to the food web could hit them hard.

The bigger lesson is that flexibility matters. Epaulette sharks stand out as models of metabolic efficiency and reproductive resilience, but the balance is delicate.

A milestone for shark physiology

This is the first study to directly measure metabolic costs of oviparity in any shark, skate, or ray. It fills a major gap in our understanding of reproductive energetics in chondrichthyans — a group long assumed to bear heavy reproductive costs.

The combination of rigorous metabolic measurements and candid discussion in Athletes of the Reef underscores how science can surprise us, even in well-studied species.

And as Dr Rummer quips in the podcast, if epaulette sharks can lay eggs with such effortless efficiency, they may just be “the ultimate budgeters of the ocean.”